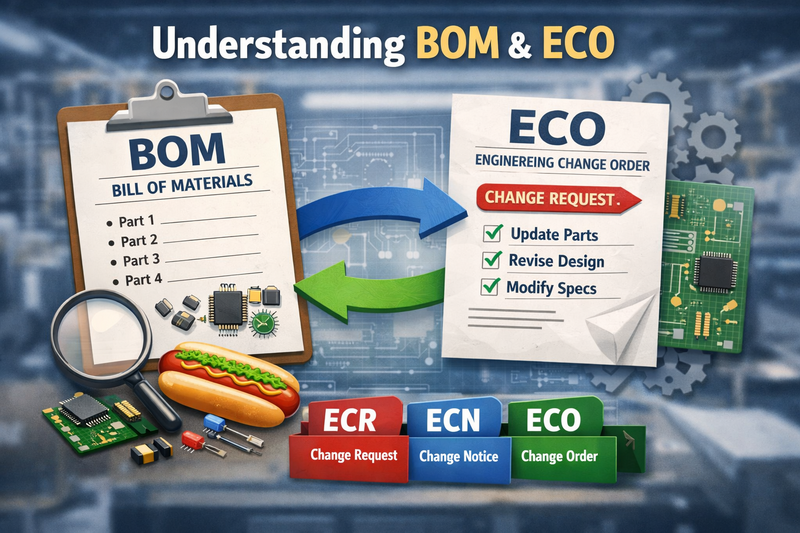

For many people who are new to the electronics manufacturing and assembly industry, BOM and ECO are two very important terms—but also two of the most confusing ones. In this article, I’ll try to explain these concepts in a simple and easy-to-understand way.

When Workingbear first entered the electronics manufacturing industry, hearing the term “BOM” for the first time was confusing. Workingbear honestly thought it had something to do with “bombing” (don’t laugh 😄). “ECO” was even more confusing—though it was obviously not the “ECO-Navi” energy-saving mode often seen in air conditioner ads or car commercials.

Time flies. Now Workingbear is already a seasoned professional, and these terms feel completely natural. Recently, however, some new employees asked Workingbear what a BOM is and how it relates to ECO, ECN, and ECR. That suddenly reminded me how difficult these concepts can be for people without factory experience.

After thinking it through again and again, here is what Workingbear believes is the clearest explanation of BOM, ECO, ECN, and ECR. If this still doesn’t make sense… then I’ve really done my best 😅 You may need to ask other experts for an even better explanation.

BOM (Bill of Materials)

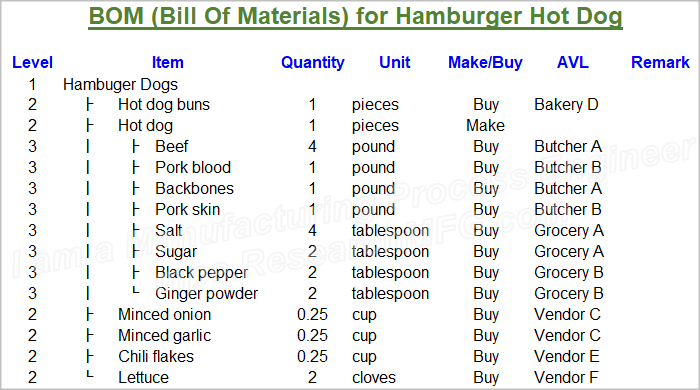

A BOM (Bill of Materials) is a complete list of all parts and materials required to build a product. It’s very similar to an ingredient list in a cooking recipe—it tells you everything needed to make the dish.

In principle, the items in a BOM are materials that need to be purchased. Using a hot dog as an example, parts would be things like the bun, lettuce, onions, chili, and so on. Sub-assemblies can either be purchased or pre-assembled in-house. In cooking terms, the sausage itself could be homemade or bought directly from the market.

Recommend reading: Why a BOM (Bill of Materials) is Critical in Electronic Product Development

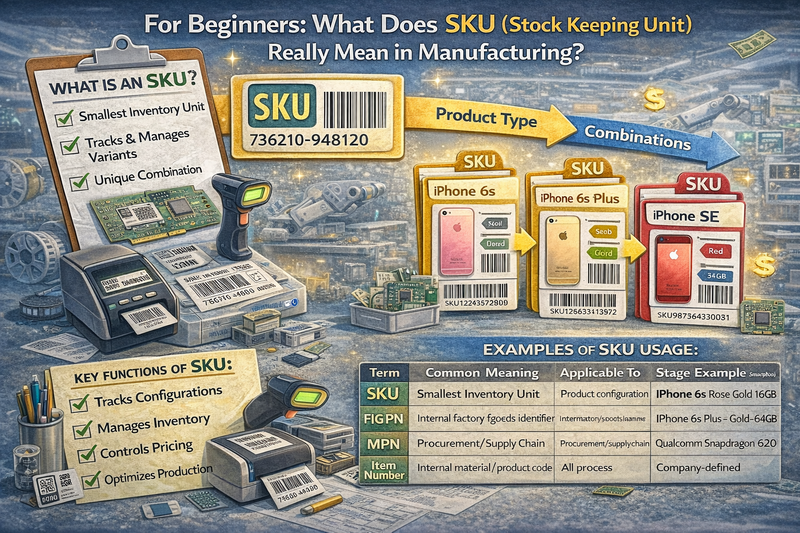

A typical BOM doesn’t just list part names and part numbers. It usually also includes quantities, units, supplier information (where to buy the part), specifications, and sometimes even placement locations. In some companies, the BOM may also include assembly flow charts or work instructions. With a complete BOM, production can usually proceed by following the assembly instructions.

Most BOMs are structured hierarchically, with parent parts and child parts. For example, the “hot dog” is the parent item, while pork, beef, salt, sugar, pepper, and spices are child items. Using smartphone assembly as an electronics example, the parent item in the BOM is the complete mobile phone, and the child items include the housing, buttons, camera module, display, battery, and the assembled printed circuit board (PCBA). Compared to a flat, single-level BOM, this hierarchical structure helps the production line clearly understand what materials are used to make each sub-assembly—so no one accidentally puts beef bones directly into a hot dog bun. That would be embarrassing.

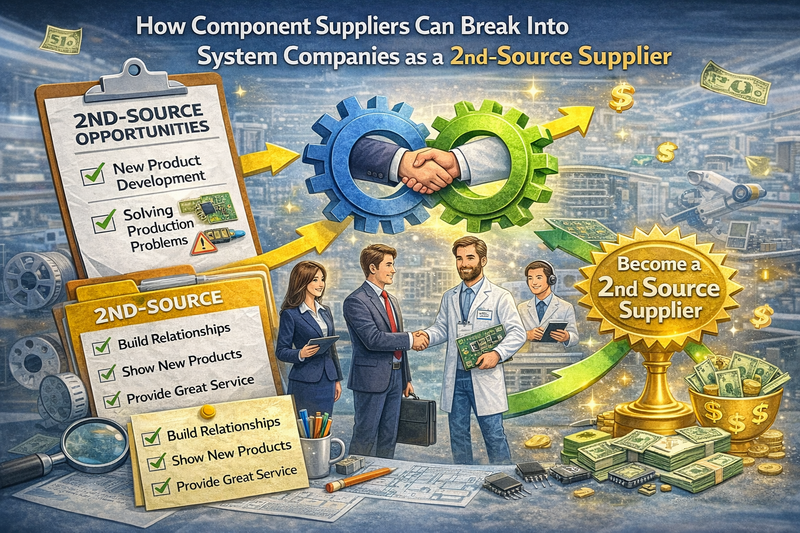

However, BOMs often need to be changed and maintained. Materials may be out of stock, costs may need to be reduced, or the product design itself may change. For example, pork might be replaced with chicken, mixed meat, or even plant-based meat. This is where the concept of second source (2nd source) comes in. It is recommended to use professional PLM software to manage and maintain BOMs to reduce human error. Of course, you can use Excel for simpler cases, but at the very least, a second person should double-check the data. BOM mistakes can sometimes lead to very serious consequences.

Another advantage of a hierarchical BOM is that factories can sell pre-assembled modules as spare parts or for after-sales service. Using the hot dog example again, if the shop makes its own sausages, it can sell sausages directly instead of selling raw pork, salt, and spices. Most customers don’t have the tools or know-how to make a sausage themselves. Back to the smartphone example, a PCBA is also something customers cannot assemble on their own. In other words, for assemblies that require special tools or processes—such as ultrasonic welding or adhesive bonding—it is best to assemble them in the factory before selling. This not only reduces customer trouble but also helps ensure quality when parts are replaced.

ECO (Engineering Change Order)

As mentioned earlier, BOMs sometimes need to change—but they can’t be changed casually. Otherwise, one person might change part A to B today, and another might change B to C tomorrow, leading to complete chaos.

That’s why any BOM change must go through a formal ECO (Engineering Change Order). This aligns with ISO document control principles: all engineering changes must be documented and approved. In other words, BOMs should be managed by rules and systems—not by personal decisions that others don’t know about, which can eventually cause quality issues.

An ECO document must clearly state the reason for the change and the updated BOM content. Before it becomes effective, it must also be reviewed and approved by relevant personnel. This helps prevent unilateral decisions—though, to be honest, top management sometimes still gets a free pass 😔.

In addition to ECO, there are also ECR (Engineering Change Request) and ECN (Engineering Change Notice).

-

ECO is usually initiated by the R&D or engineering team, since design engineers understand their products best and are responsible for them. In some companies, post–mass production maintenance is handled by a CE team (Concurrent Engineering or Continuous Engineering). As long as a department is responsible for BOM maintenance, it can issue an ECO after proper approval.

-

ECR is typically raised by people who do not have the authority to issue an ECO. For example, a process engineer in an assembly factory may request a design or BOM change to improve manufacturability. In this case, they submit an ECR. Once approved, the BOM owner then issues the official ECO.

-

ECN is usually issued by the DCC (Document Control Center). It serves as a notification to inform relevant teams that a BOM or document has changed—for example, notifying purchasing to buy new materials or informing production to switch components. The main goal is to ensure everyone is working with the same, up-to-date information. In the automotive industry, ECNs are more commonly used for supply chain notifications, while in the electronics industry they are often integrated directly into PLM systems.

Some companies use ECO and ECN interchangeably. In the internet era, the difference has indeed become smaller. Modern PLM or ERP systems automatically notify all relevant departments once an ECO is approved, so a separate ECN is often unnecessary.

Today, most companies use PLM (Product Lifecycle Management) systems to manage BOMs and documents digitally. ECO approval and notifications are fully computerized. At Workingbear’s company, for example, Agile application is used to manage all BOMs and documents, with updates synced daily to Oracle. When a BOM changes, Agile sends out email notifications, and people simply check the system. As a result, the distinction between ECO and ECN has gradually become blurred.

In short, the BOM is the core list behind product manufacturing, while ECO, ECR, and ECN ensure that changes are managed in a controlled and orderly way. Understanding these concepts will help you work more smoothly in the electronics manufacturing industry.

Related Posts:

Leave a Reply