The “8D report” is a tool commonly used in the electronics assembly industry for “problem analysis and solving.” Due to its systematic and clear steps, the “8D report” is often utilized in responding to customer complaint cases.

The term “8D” refers to the “8 Disciplines process.” The person filling out the report generally follows predefined steps in sequence. This helps most quality control personnel systematically identify the causes of problems step by step. It also allows you to explain to the customer how the problem was discovered or occurred, how you analyzed the problem, found the root cause, verified if the problem was genuinely resolved, and implemented preventive measures to prevent the problem from recurring.

In essence, the “8D report” is quite similar to “QC Story” and DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control), just with a slightly different name. Spiritually, it is the same — establishing a systematic approach and following a logical order to help users clarify and solve problems. It also serves as a record for future reference.

There are various formats for the “8D report,” but the methods are essentially similar. Once you grasp the rhythm and key points, you’re good to go. In the following, I’ll briefly explain the content of the “8D report.” However, due to limited space, a comprehensive understanding might require a 5-6 hour class at a quality institute. This article provides a rough explanation of its essence.

Discipline 1: Form the Team

Members of an 8D team usually come from different departments. There isn’t a strict rule for who should join, but the team is typically formed based on which departments are involved in the customer’s complaint.

For example, in an electronics assembly factory, if the issue is product quality, the team usually includes:

-

Quality Control (QC) and Quality Assurance (QA): QC usually handles internal quality, while QA deals with external issues. QA is often the team leader, responsible for responding to the customer.

-

Process: Works with product assembly and process steps. Usually tasked with identifying where the process might be going wrong.

-

Testing: Supports product testing. Typically responsible for figuring out why existing test methods failed to catch defective products.

-

Production: Works with manufacturing tasks. Often asked to run experiments or collect data to help identify issues and support solutions.

-

Sometimes R&D and Facility teams may also be involved, depending on the problem.

Every 8D team needs a leader. Usually, QA is chosen since they directly face the customer. But in my experience, QA tends to be “soft” and has trouble pushing other departments. Since I come from a Process background, I’ve seen most cases where Process ends up leading the team. Ideally, the team should also have a Champion/Sponsor—someone with real decision-making authority in the company. This person doesn’t need to attend every meeting but can step in to remove roadblocks when needed.

Each meeting should also have a recorder. It’s best to assign this person before the meeting starts, and afterward, they should send out meeting notes to every member so everyone is clear about the conclusions and their assigned tasks.

I know some companies form an “8D team” with just one person, but that’s not really solving problems—it’s just producing a report for show.

Discipline 2: Describe the Problem

It’s a good idea to use 5W1H method (Who, What, Where, When, Why, How) when describing the problem. This helps the team clearly understand when and where the issue happened, what exactly went wrong, how serious it is, the current status, and what was done as an immediate fix.

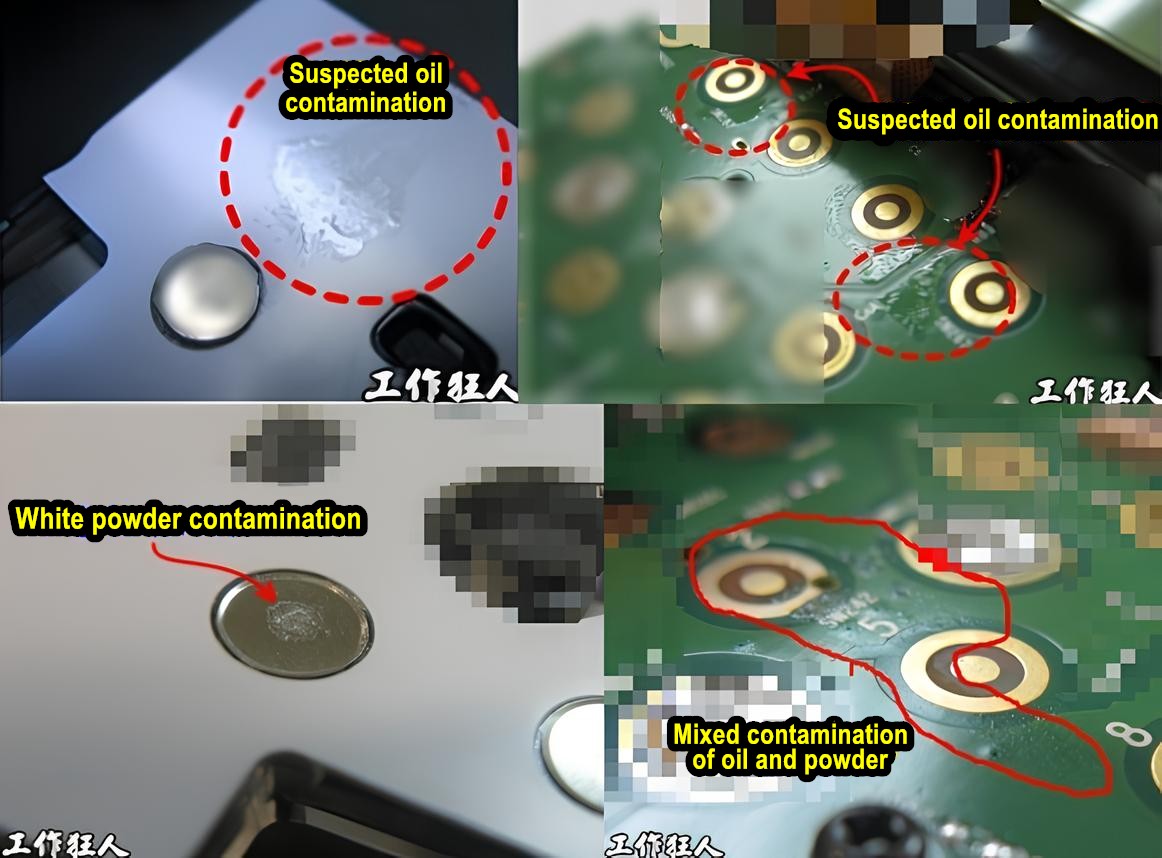

If possible, show photos or evidence from when the issue happened, along with data you’ve collected. The more quantitative the information, the better—avoid vague statements like “it got much better.” Think of yourself as a CSI investigator: the clearer you present the evidence and details, the faster the team can understand the situation and solve the problem.

It’s also helpful to prepare a flow chart of the product’s process. This can make it easier for team members who aren’t familiar with the process to quickly catch up and understand where the problem might be.

Discipline 3: Contain the Problem

When a problem arises, regardless of whether the root cause is identified, immediate actions must be taken to contain the issue. This involves implementing necessary temporary solutions, such as screening out problematic products at the customer’s end or replacing defective items for the customer to continue production or shipment.

On the manufacturing end, measures should be taken to prevent the continued occurrence or shipment of problematic products, such as replacing production machinery, intensifying screening, implementing full inspections, switching from automatic to manual processes, conducting inventory checks, and more.

At this stage, one serious problem often comes up: the normal inspection process fails to catch defective products. This usually happens with unusual or never-before-seen defects, which can end up slipping into the customer’s hands. That’s why the sorting or screening process may need to be tightened or even redefined. The key is to make sure the screening method is truly effective.

Once temporary countermeasures are decided, they should be promptly delegated to team members for execution, with continuous reporting on their effectiveness.

In more disciplined teams, this stage also includes another round of risk analysis. The goal is to evaluate how far the problem spreads, determine how serious the impact is, and figure out what level of corrective action is needed to contain it. For example:

- Is the defective part or product limited to a single batch, or does it affect multiple batches?

- Does it only impact a specific customer, or all shipments?

- Is it confined to one production line, or showing up across multiple factories?

Discipline 4: Identify the Root Cause

Workingbear has noticed that many people get stuck at this stage. It’s true—this is the toughest part of an 8D Report. But there are plenty of quality tools we can use to systematically uncover the problem and find the true root cause.

Workingbear has noticed that many people get stuck at this stage. It’s true—this is the toughest part of an 8D Report. But there are plenty of quality tools we can use to systematically uncover the problem and find the true root cause.

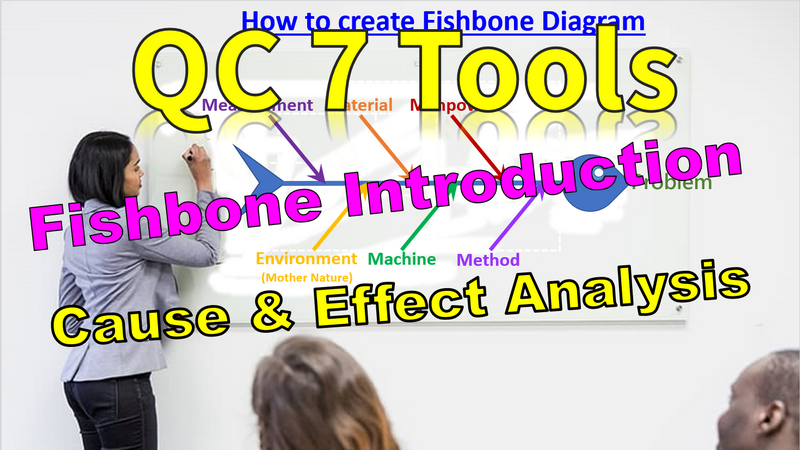

One of the most common tools is the Cause-and-Effect Diagram (Fishbone Diagram or Ishikawa Diagram). It reminds us to look at six main categories: Man (People), Method (Process), Material, Machine, Measurement, and Mother Nature (Environment). By going through each one, we can check for changes before and after the issue appeared. For example: Did staffing change? Was the work method altered? Did the supplier switch materials? Was a fixture replaced? Could it be related to temperature or humidity in the environment?

Another useful tool is the Pareto Chart, which helps us collect and analyze which problems should be prioritized.

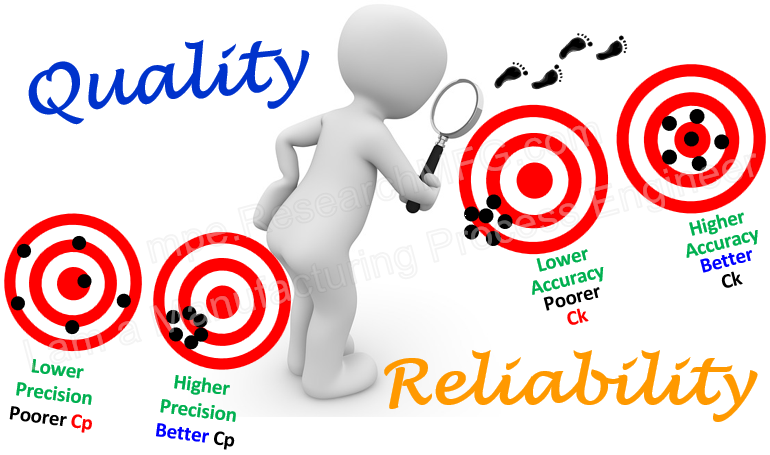

From experience, factories that collect daily operational data are much faster at finding the true cause. Examples include repair logs, Cpk (process capability) reports, or real-time yield tracking systems. We can also use designed experiments (DOE) to find the best process parameters.

Some engineers use a Why Tree, tracing the issue step by step based on engineering experience until they reach the most fundamental cause.

Once a possible root cause is identified, we must do one very important thing: verify it. The suspected cause is only a hypothesis—we need to confirm it. The best way is to reproduce the defect through simulation. Only then can we be sure we’ve found the real cause.

For example, if IC leads are bent due to a damaged mold, replacing the mold fixes the problem. To verify, we reinstall the damaged mold. If the same defect happens again, then the cause is confirmed. But if the defect doesn’t reappear, the mold might not be the true cause, and we’ll need to keep investigating.

👉 Related reading: SPC, Cpk, and Process Capability Explained

Also, if the problem is caught by the customer or only discovered later in the process, we need to ask an additional question: Why was it missed? In other words, why wasn’t it stopped earlier? This is called the “escape point” analysis (Why-escaped). Later steps shouldn’t just fix the root cause, but also address why the defect escaped detection in the first place.

Once the true root cause is identified, it’s a good practice to also check whether other products face the same risk. For example, if the issue comes from defective incoming materials, are other products using the same materials also at risk? Or, could other materials from that supplier carry the same potential problem?

When providing corrective actions, here’s a small tip to keep in mind: your improvement plan must be clear and specific. It’s best to define it using measurable numbers or standards so the action can actually be implemented, instead of just sounding good on paper.

For example, some people often use a vague phrase like “strengthen employee training” to address operator mistakes. But this kind of description is too general and will easily be questioned. A better approach is to clearly list the training content, evaluation frequency, pass criteria, and even the assessment method.

Another common example is writing “tighten inspection frequency” to prevent defects from escaping. This is also not specific enough. It’s recommended to quantify it, such as: the original X-Ray sampling rate was 2 units per hour, and now it’s increased to 4 units per hour. This type of description makes it easier to evaluate the effectiveness and is more auditable.

In short, when writing corrective actions in D4, avoid vague, generic, and unquantifiable statements. This makes the improvement plan more convincing and helps prevent the report from being rejected later.

Discipline 5: Formulate and Verify Corrective Actions

Once we’ve found the true root cause, we can start planning corrective actions. There may be several possible solutions—such as repairing, adjusting, or upgrading a mold. Each option should be weighed with pros and cons, such as:

-

How much cost and manpower will it take?

-

How long will the improvement last?

-

Could there be negative side effects?

If possible, use a scoring method like FMEA to evaluate the risks and prioritize the best corrective action.

Before rolling out the corrective action company-wide, it’s important to run a trial implementation (like a pilot run or small-scale test). This confirms the fix really works and won’t create new problems for other products, processes, or quality factors.

Why? Because process parameters often affect each other. For example, if IC lead deformation was caused by a worn mold, we might switch to a harder mold material. A trial run shows the new mold lasts longer, but now it leaves extra marks on the IC leads because it’s too hard. That’s a side effect—meaning we need to go back, re-evaluate, and adjust the solution.

Discipline 6: Correct the Problem and Confirm the Effects

Once the trial run proves that the corrective action works, it’s time to roll it out fully in production. But that doesn’t mean we can relax right away. We still need to closely monitor the process, collect data over a period of time, and use statistical tools—like run charts or control charts—to compare before and after results. This helps confirm whether the corrective action really made a significant improvement. If possible, apply SPC methods to ensure the process is truly under control.

If there are multiple corrective actions, it’s best to implement them one by one, collecting data for each. This way, it’s clear which action produced which effect.

Only when the permanent corrective action has been proven effective and stable can we safely remove the earlier temporary fixes.

Discipline 7: Prevent the Problem

After confirming the corrective action works, the next step is to make sure the same issue doesn’t come back—and that it doesn’t pop up in other products or processes either. This requires standardization, documentation, and horizontal deployment:

-

Update related documents: Revise SOPs, work instructions, and inspection standards so the new method becomes part of everyday operations.

-

Revise quality system files: Update tools like FMEA, Control Plans, and Inspection Plans so the improvements are built into the quality management system.

-

Training and education: Train operators and engineers so everyone understands and follows the new way of working.

-

Supervision and audits: Use internal audits or routine checks to make sure the corrective actions are actually being followed, preventing a return to old mistakes.

-

Horizontal deployment: If the same issue could happen in other products or processes, roll out the same corrective action there as well.

By doing this, we not only prevent the problem from happening again, but also strengthen the overall stability of quality management.

Discipline 8: Congratulate the Team

Acknowledge and commend team members who put in efforts to solve the problem. It fosters a sense of accomplishment in their work and a willingness to tackle future challenges.

Related Posts:

Leave a Reply